Author:Shi Haitao

⚠️Safety Alert

-

Priority Contact with Diplomatic Missions: When the reliability of local police cannot be verified, immediately contact the Chinese embassy or consulate in the area and provide:

✅ Precise geolocation information

✅ On-site environmental photos - Effective Strategy: Using diplomatic missions to exert pressure on local law enforcement significantly increases rescue success rates.

- Risk Warning: Directly seeking help from local police may result in forced return to fraud compounds ⚠️ substantially raising the risk of secondary harm

Preface

The pleas for help from Chinese citizens abroad have pierced through national borders, tearing away the veil on Southeast Asia’s “legal governance vacuum zones (法治无人区)” – regions that serve not only as sanctuaries for criminals but also as gray testing grounds for great power competition. A series of Chinese-related fraud compounds (涉华诈骗园区) incidents in Myanmar in recent years reveals profound transformations in contemporary transnational crime. This evolution manifests not only through technologically-enhanced criminal tactics but also exposes deep-seated dilemmas in regional geopolitical dynamics and governance mechanisms.

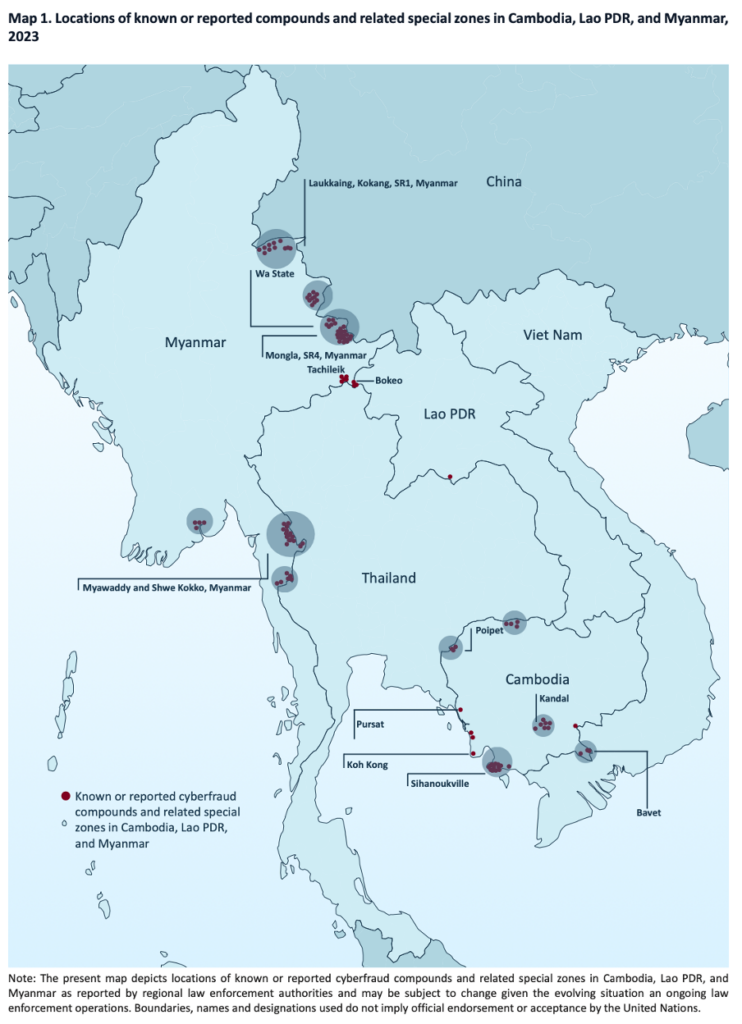

Through the dual lenses of criminology and international relations, we observe criminal syndicates demonstrating remarkable “流动性生存” (fluid survival) capabilities, akin to an endless game of whack-a-mole. Each time a criminal hub is dismantled, new fraud centers emerge like fungal spores in alternative locations. This phenomenon of crime displacement operates within Southeast Asia’s unique geopolitical ecosystem – where warlord fiefdoms, economic dependencies, and great power rivalries weave intricate “crackdown-and-protection” networks across military junta governance gaps. When a Myanmar border checkpoint officer simultaneously shoulders dual responsibilities of combating crime and maintaining “fraud compound economies”, international law enforcement cooperation becomes insufficient to eradicate this systemic malignancy.

Simultaneously, China’s economic investments and strategic interests in Myanmar form a perverse counterbalance to the monthly occurrence of thousands of cross-border fraud cases. Although United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) reports commend China’s achievements in citizen protection and transnational anti-fraud operations, uprooting this persistent thorn requires re-examining the core drivers of criminal ecosystems.

The Routine Activity Theory proposed by Marcus Felson and Lawrence E. Cohen provides a crucial analytical framework. This theory identifies three essential elements for criminal behavior: 1) A motivated offender, 2) A suitable target, 3) The absence of capable guardianship. Although initially developed to analyze direct-contact predatory crimes, the theory offers valuable insights for studying cybercrime. As noted by Peter Grabosky, beyond its transnational nature, cybercrime essentially represents “old wine in new bottles” – traditional criminal patterns adapted to the digital age. Regarding telecom fraud prevention, given the persistent challenges in eliminating criminal motivations and establishing effective oversight, strategic focus should emphasize protecting “suitable targets.”

This article will briefly analyze the evolutionary logic of telecom fraud crimes in northern Myanmar, the challenges of cross-border law enforcement by China, and the corresponding strategies from three perspectives: criminal displacement, two-level games theory, and social prevention mechanisms.

01

Crime Displacement:

Cross-border Migration and Evolution of Fraud Operations

Crime Displacement Theory offers a critical lens for understanding the transnational migration of fraud operations. A classic analogy for this theory is “squeezing a balloon” – when law enforcement intensifies crackdowns in one region, criminal activities do not vanish but instead “rebound” to areas with weaker controls. More alarmingly, crime displacement extends beyond geographical shifts; criminal patterns undergo “genetic mutations” as environments evolve. In Myanmar, the original “telecom fraud gene” completed its primitive accumulation in specific socioeconomic soil. Following the pandemic and subsequent crackdowns, it began rapid evolution: from forced labor to organ trafficking, human smuggling to transnational money laundering. These derivative crimes intertwine like vines, forming a self-sustaining criminal ecosystem. Modern fraud syndicates now employ blockchain technology for money laundering, recruit members via the dark web, and even use AI voice cloning to impersonate victims’ family members. Such tech-driven adaptations render traditional law enforcement tactics increasingly obsolete. Of particular concern is the emergence of “path dependence” within criminal organizations. Once a crime model proves successful, these groups become locked into reinforcing and expanding their operations along established pathways.

The Plague-like Spread of Fraud Hubs:

From Northern Myanmar to “Northern Myanmar+”

In August 2023, some Chinese telecom fraud syndicates, having endured intensified crackdowns, gradually “relocated” to northern Myanmar.

Subsequently, even as the spotlight of law enforcement shifted to northern Myanmar and dismantled the four prominent clans in Kokang (果敢四大家族), the specter of telecom fraud never truly dissipated. It simply possessed new actors, continuing to enact criminal schemes on different stages.

Myawaddy has emerged as the prime relocation site for telecom fraud syndicates. The region offers unique advantages for establishing fraud compounds. Situated on the Myanmar-Thailand border just 500 kilometers from Bangkok, this logistical advantage functions as an express lane for criminal operations. Separated from Thailand’s Mae Sot by the narrow Moei River, these waters transport not just goods but also human trafficking victims via speedboat smuggling. Currently controlled by ethnic armed groups like the Karen National Union (KNU), Myawaddy’s shadowy financial ties between militias and criminal networks have transformed this lawless enclave into a “breeding ground for crime.”

Satellite imagery reveals the shocking reality: The Myawaddy Border Trade Zone – under whose guise the notorious KK compound operates – provides criminal enterprises with legitimate commercial cover. Its robust telecommunications networks, stable power supply, modern infrastructure, coupled with cross-border capital flows and dense commercial activity, create ideal conditions for fraud operations. The transboundary geography and collusion between local militias and criminal organizations significantly complicate international law enforcement coordination.

Beyond Myawaddy, evidence indicates numerous fraud groups have shifted operations to Dubai, exploiting its relatively lax oversight. Here, opulent villas mask blood-stained dungeons in a grotesque “dream-making” enterprise. Job seekers lured by ads promising “100,000 dirham monthly salary + private pool” never anticipate the reality: iron cages in desert compounds and the threat of being transformed into “human jerky” under the relentless sun.

The Crimson Evolution of Criminal Modus Operandi:

From Fraud to “Fraud-Plus”

Myanmar’s criminal transformation traces back to 2003. Prior to this watershed year, many locals relied on drug-related industries for survival. In the spring of that year, when the axe of drug prohibition fell with full force, local armed groups were compelled to shift from narcotics operations to casino businesses to sustain military expenditures.

Surprisingly, this industrial transition awakened a savage genetic code of violence. The land of Kokang began enacting darker narratives. Farmers who once bent over poppy fields, deprived of income, discarded their hoes and picked up machetes to violently rob visiting gamblers. As gambling-related “losing money and life” incidents proliferated, coupled with the booming casino industries in neighboring Thailand and Vietnam, northern Myanmar’s gambling sector fell into crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic served as the final hammer blow, shattering Myanmar’s already crumbling casino economy.

Twists of fate often carry a dark humor. Fraud syndicates fleeing China’s intensified crackdown formed new symbiotic relationships with local armed groups in Myanmar: the armed factions provided protection for scamming operations in exchange for profit shares. What initially appeared as routine cooperation gradually transformed as the armed groups recognized that telecom fraud profits far exceeded their previous revenue streams. Some gradually became shadow operators themselves.

As hundreds of millions of Chinese citizens saw red warning alerts from the Anti-Fraud App (反诈APP) light up their phones, fraud tactics in Myanmar’s industrial compound underwent frenzied evolution. With declining success rates in scams, deceptive recruitment became necessary to expand operations and profits. Job postings transformed into human traps, military-style management escalated into modern slavery, and organs of failed fraudsters became the final exploitable resource. From scam scripts to organ refrigeration units, this bloody metamorphosis reveals a harsh reality: in governance vacuums, criminal organizations continually adapt their operations under external pressures, even developing sanguinary proliferation methods to ensure survival and expansion.

The Path to Professionalization Empowered by High Technology:

From Physical Deterrence to Memory Reconstruction

The modern telecom fraud industry has evolved sophisticated hunting techniques that blend technology with human psychology. Fraud syndicates have established comprehensive criminal networks encompassing technical support, script training, and specialized division of labor. Technologically, they utilize VPNs and encrypted communication tools to evade detection, even employing AI-generated realistic voice and imagery for scams. While big data and AI have enhanced fraud monitoring capabilities, criminals adapt rapidly – modifying scripts when systems detect suspicious patterns, or switching domains after blacklisting. This “cat-and-mouse game” renders technological countermeasures often temporary in effectiveness. Regarding psychological manipulation, He Zhendong, a survivor from northern Myanmar interviewed by Phoenix News, revealed systematic training in specialized techniques like “refined chatting (精聊)”, “detailed chatting (细聊)”, “opening lines (开场白)”, “Down-to-earth sweet talk (土情话)”, and “dream-weaving (造梦)” to precisely target victims.

Emerging platforms like social media and live-streaming have enabled customized fraud scenarios across all digital spaces – from dating app “perfect partners” to get-rich-quick schemes on Kuaishou (快手). The Wang Xing recruitment scam case exemplifies targeted strategies against job seekers. Undercover materials show fraud scripts incorporating anime memes for Generation Z, while replicating 1980s supply-and-marketing-cooperative rhetoric (供销社话术) for elderly targets. As we marvel at deepfake realism, greater vigilance is needed: when scams shift from exploiting technical flaws to cognitive gaps, society’s psychological immunity faces unprecedented challenges.

02

China’s Cross-Border Law Enforcement Dilemma

While Chinese police vigorously promote “anti-telecom fraud campaigns” through various channels, the relentless clatter of keyboards continues day and night in Myanmar’s scam compounds. This surreal reality vividly illustrates the challenges of cross-border law enforcement. Robert Putnam’s “Two-Level Games theory” provides a valuable framework for understanding this complex chess match.

On the international chessboard, China faces a dual imperative: maintaining diplomatic principles of non-interference to avoid criticism from Western media, while simultaneously preserving strategic and economic interests in Myanmar through measured diplomatic engagement with its military regime.

Domestically, distressing rescue videos from trapped Chinese citizens in Myanmar strike raw nerves nationwide. When emotional appeals rooted in “blood ties” collide with geopolitical calculations, policymakers must navigate a delicate balance – striving to protect both national interests and vulnerable citizens through holistic approaches.

Absence of Regulatory Oversight:

The Dilemma of International Law Enforcement Cooperation

It is undeniable that news of successful multinational law enforcement operations frequently dominates media headlines, bringing a sense of triumph and reassurance. For instance, in September 2024, China and Myanmar jointly apprehended 20 leaders of telecom fraud syndicates in Yangon and Mandalay. In October of the same year, China and The Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) issued a ASEAN-CHINA JOINT STATEMENT ON COMBATTING TELECOMMUNICATION NETWORK FRAUD AND ONLINE GAMBLING. These developments demonstrate multilateral governments’ determination to combat transnational crime through regional cooperation. However, translating commitments on paper into concrete actions remains a long-term challenge.

When joint law enforcement forces establish high-pressure crackdowns at specific geographic coordinates, the aforementioned “balloon effect” inevitably emerges. This phenomenon reveals how modern criminal organizations have developed acute sensitivity to geopolitical fault lines, often detecting discrepancies in policy enforcement faster than law enforcement agencies themselves. This reality demonstrates that mere collaborative policing might only displace criminal activities across regions rather than achieving comprehensive eradication.

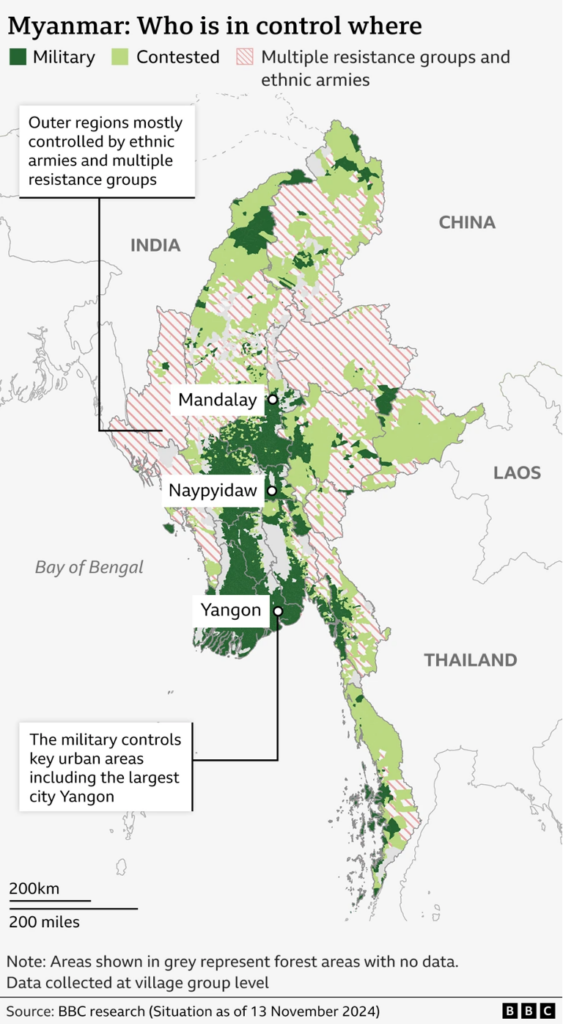

The proposed “comprehensive prevention and control system” (全方位防控体系) by some experts appears inadequate when confronted with Southeast Asia’s intricate political landscape. Taking Myanmar as a primary example: This nation of 135 ethnic groups features an interlocking mosaic of territories controlled by local armed groups and central government jurisdictions. Merely establishing functional extradition agreements requires navigating a threefold obstacle course involving warlords, ethnic armed organizations, and the military junta. Given Myanmar’s complex political dynamics and legal disparities with neighboring countries, substantive breakthroughs are unlikely in the short term.

Furthermore, the political instability and weak governance capacity prevalent in several Southeast Asian nations show little prospect of immediate improvement. Translating the vision of coordinated regional governance enhancement from concept to practice must overcome multiple systemic barriers. These structural challenges render the transition from targeted crackdowns to comprehensive governance exceptionally arduous across the region.

Regulators’ Entangled Interests:

The Jurisdictional Power Dynamics of Cross-Border Law Enforcement

On September 30, 2023, when self-media blogger Hu Qi Dao’s volunteer rescue team received a call for help, armed with guns, and drove a Land Cruiser down a dirt road along the Thai-Myanmar border, they were worried that they would be recognized by the Myanmar police at the Mae Sot border crossing, which would have tipped off the fraudulent compounds and made the rescue operation futile. This incident reveals Myanmar’s complex political landscape, where a legal vacuum fosters collusion between law enforcement and criminal syndicates.

Sources along the Thailand-Myanmar border disclose that although fraud compounds operate within Myanmar, critical infrastructure including power grids and construction materials are primarily supplied through Thailand. The much-publicized rescue of Wang Xing, ostensibly a “heroic rescue operation” by Thai police, may have been staged after backchannel negotiations with the Karen Border Guard Force (克伦边防军) to secure the release. German media investigations further exposed that six key operators behind the Myawaddy scam networks reside in Bangkok. These revelations starkly contrast with Thai authorities’ public declarations of “cracking down on telecom fraud,” rendering such claims increasingly hollow.

Some analysts have pointed out that if Thailand were to unilaterally sever the supply of materials to the fraud compounds, merely depriving them of food and internet for one month would render these criminal dens unsustainable. Images of Thai Prime Minister Paetongtarn smiling and raising a toast in Beijing to welcome Chinese tourists to Thailand continue to circulate. Meanwhile, the roar of diesel generators in the fraud compounds seems to mock the Thai government’s power-cut order for Myawaddy. On the night of the blackout, residents along the border captured footage showing that the scam region remained brightly lit. There are even reports that the scam zones have already acquired “Starlink” equipment on the black market to avoid being cut off from the internet.

The failure of this policy may stem from Thailand’s unique power structure: under its constitutional monarchy, the royal family still retains significant power. Although the elected government leads administrative operations, the military—loyal to the royal family—continues to control the core military power. Since the 1932 constitutional revolution, the military has launched roughly 13 successful coups, creating a cyclical pattern of “military rule → democratic elections → military coups.” This structural contradiction has often reduced the elected government to a mere puppet in the power game—whenever the civilian bureaucratic groups attempt to push for military reform, the military seizes the opportunity to invoke the pretexts of “protecting the royal family”, “national stability”, and “combating corruption” to safeguard its own power and interests, thereby rebooting the political reshuffling.

It is undeniable that severing the economic lifeline of telecom fraud syndicates could be a viable strategy. However, in Thailand, various power factions are driven by gray economic interests. Under such a complex web of interests, whether the elected government’s crackdown on telecom fraud can secure military support remains uncertain, and the actual effectiveness of these measures warrants close observation.

Balance on the Geopolitical Chessboard: Strategies for Transnational Power Games

China maintains significant economic and strategic interests in Myanmar. The flickering numbers on the control panels of the China-Myanmar Oil and Gas Pipeline (Rakhine State to Yunnan) are quietly redrawing Asia’s energy map. This “energy lifeline” annually transports 22 million metric tons of crude oil and 12 billion cubic meters of natural gas to China. Under the Belt and Road Initiative, the Kyaukphyu Deep Sea Port in Rakhine State operates around the clock, with cranes loading and unloading cargo. This strategic infrastructure reduces China’s reliance on the Malacca Strait while creating a vital gateway to the Indian Ocean. Additionally, Myanmar’s abundant rare earth deposits and copper ore reserves are becoming crucial resources supporting China’s intelligent manufacturing ambitions.

Although Myanmar’s military junta currently controls only 21% of the country’s territory, it maintains authority over 59% of urban areas and critical infrastructure – making it the key stabilizing force. China’s pragmatic approach follows a clear principle: we cooperate with whoever can ensure Myanmar’s stability. This explains Beijing’s engagement with the military government. Another strategic consideration involves the National Unity Government (NUG) backed by Western powers. Should this opposition group gain power, it might repudiate agreements signed during military rule and historical debts, potentially jeopardizing Chinese investments. Within this complex geopolitical chess game, China must continually reassess existing cooperation frameworks while guarding against emerging strategic vulnerabilities.

On the flip side, telecom fraud has become a crucial funding source for Myanmar’s military junta to sustain its military expenditures, explaining why China’s repeated requests for cooperation in cracking down on scam compounds in northern Myanmar have been ignored. To rescue trapped Chinese citizens and eradicate these criminal hubs, the Chinese government has been compelled to collaborate with Myanmar’s Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs). Notably, under sustained Chinese pressure, the “Three Brotherhood Alliance” – composed of the Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), Arakan Army (AA), and Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) – launched a military operation on October 27, 2023 under the banner of “eliminating telecom fraud syndicates.” This campaign ultimately toppled the “Four Great Families” that had long controlled the Kokang region.

However, this operation produced unintended consequences. Ethnic armed groups discovered the military junta’s vulnerability, exposing it as a veritable “paper tiger.” Emboldened by their success, these groups seized substantial territories and gained control over major rare earth mining areas. Despite China’s attempts to pressure ethnic militias into halting their offensive against the junta, hostilities resumed in June 2023 after a brief ceasefire from January to May. On January 20, 2024, China’s Foreign Ministry announced it had brokered another ceasefire agreement. Nevertheless, such temporary truces are unlikely to resolve fundamental issues.

In summary, under the Belt and Road Initiative framework, China faces the challenge of balancing cross-border crime suppression with safeguarding economic interests. The complex geopolitical landscape continues to complicate Chinese policymakers’ operational calculus in the region.

03

Crime Prevention Strategies:

Getting to the Social Root Causes

Compared to traditional crimes, cybercrime demonstrates “advantages” in target selection mechanisms. Its non-contact nature breaks geographical constraints, enabling criminals to conduct indiscriminate network-wide attacks through distributed nodes. This technology-enabled scaling effect of crime directly drives criminal organizations to continuously expand human resources, transporting large numbers of people to telecom fraud compounds through deception or coercion to establish industrialized fraud assembly lines. Therefore, under the dual challenges of persistent criminal motivations and Myanmar’s internal regulatory gaps, governance strategies should shift from “source blocking” to enhancing the “immunity” of potential victim groups through multi-dimensional interventions.

When examining various telecom network fraud prevention manuals, an unsettling paradox emerges behind these neatly organized guidelines: the primary audience for such educational materials tends to be those already possessing security awareness, while the groups most in need of this knowledge often miss these warnings in the information deluge. For instance, unemployed individuals are more likely to be attracted by high-salary recruitment ads than to study twenty-page fraud prevention manuals. This misalignment in information dissemination creates a “misfire” dilemma in fraud prevention education. Furthermore, the rapid iteration and highly customized nature of fraud tactics often outpace these educational materials. Consequently, if prevention campaigns aim to keep up with evolving fraud techniques, creating short videos reconstructing cybercrime scenarios might prove more effective than distributing manuals, allowing the public to develop awareness through authentic victim narratives.

A more noteworthy fact is that a significant portion of individuals traveling to Myanmar for “employment” are not coerced but go voluntarily. This is evident in the narratives of some “victims.” For instance, social media influencer Xing Weilin, who escaped northern Myanmar, claimed during interviews to have been “drugged and trafficked”—a fabricated excuse to conceal his voluntary decision. Reaching northern Myanmar requires traversing mountainous terrain for two days through multiple checkpoints. As one human smuggler admitted: “The payout per person is only 30,000 yuan. It’s not worth antagonizing the Chinese government.” Within China’s borders, these so-called “victims” could have reported to authorities at any time, as smugglers rarely employ forceful methods. The myth of knockout drugs persists despite practical limitations: insufficient doses lead to quick recovery, while excessive amounts prove fatal. Successful border crossings only occur when individuals willingly undertake the arduous journey.

Many “victims” possess prior awareness of the illicit activities they will engage in. Economic pressures and delusions of “being the exception who strikes it rich” drive their risky decisions. This cognitive dissonance stems from a distorted success philosophy permeating society. When short video platforms glorify “overnight wealth” stories and “money-making” becomes social currency, gray-area “opportunities” acquire a deceptive allure. Such social psychological shifts render conventional anti-fraud campaigns ineffective. The “high-paying customer service” job postings we encounter reflect not just criminal ingenuity, but a generation’s collective anxiety. The fraudulent scripts recited daily by these coerced “customer service agents” often mirror the very lies they once believed themselves.

“The best social policy is the best criminal policy” – this famous maxim by German criminal law scholar Franz von Liszt profoundly reveals the intrinsic connection between social policies and crime prevention. This perspective reminds us that to fundamentally prevent crime, alongside the indispensable “iron fist” of criminal justice and the reshaping of social values, we must strengthen and improve the social security system to optimize the entire social ecosystem. Rebuilding the employment ecosystem may be the most pressing task. Governments could collaborate with enterprises to establish “skills development centers”, enabling laid-off workers to acquire new skills and restart their careers. Public welfare positions should serve as transitional stations for groups undergoing resocialization. Community grids require not just staff members, but professional social workers who bring human warmth. When psychological counselors listen to the anxieties of the unemployed in community tea rooms, and legal advisors resolve labor disputes at neighborhood service centers, these subtle yet crucial forms of support can significantly reduce the “vulnerability” of potential victims.

Conclusion

The Myanmar border telecom fraud cases reveal the complexity of contemporary transnational crime and the challenges in governance. From the perspective of crime displacement theory, sole reliance on law enforcement crackdowns tends to merely displace criminal activities rather than address root causes. Through an international relations lens, China faces the delicate balance between safeguarding national sovereignty, protecting citizens, and maintaining economic interests during cross-border anti-fraud operations.

This intricate geopolitical reality demonstrates that combating transnational fraud cannot rely on unilateral measures. Instead, it requires a comprehensive governance framework integrating international law enforcement cooperation, technological prevention measures, and social governance mechanisms. Crucially, addressing the social roots of this phenomenon is imperative. Improving employment opportunities, strengthening social welfare systems, and similar measures are essential to eliminate the breeding ground for transnational fraud crimes at its source.

(The author is a Criminologist and holds a PhD from the University of Edinburgh. He is the Co-founder and Academic Director of Science&Vision.)

Visual Design: Haitao Shi

Editor: Yue Liu

Major Events Timeline in Myanmar

Period of Protracted Conflict

Decades-long conflict between the Tatmadaw (Myanmar military) and Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs). China established strong economic and military ties with Myanmar, investing heavily in infrastructure and resource extraction projects, particularly as part of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC).

Military Coup

The Tatmadaw staged a coup overthrowing the democratically elected National League for Democracy (NLD) government led by Aung San Suu Kyi. The National Unity Government (NUG) subsequently formed as a shadow government composed of deposed representatives. People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) organized nationwide, sparking widespread resistance movements. China maintained contact with the junta while publicly opposing the coup.

Intensified Civil War

Civil war escalated with the Tatmadaw facing increasing resistance from EAOs and PDFs. Transnational criminal activities including cyber scams and human trafficking proliferated, particularly in border regions adjacent to China.

Chinese Diplomatic Intervention

Chinese diplomats visited Myanmar urging the junta to address cross-border criminal activities originating from its territory.

Myawaddy Attack Incident

Myawaddy police station bombed by drone, resulting in 3 deaths including the chief, and over 10 injuries.

Launch of “Operation 1027”

On October 27, the Three Brotherhood Alliance (Arakan Army, Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army, and Ta’ang National Liberation Army) initiated Operation 1027 against the junta in northern Shan State, simultaneously targeting telecom fraud. The operation led to the collapse of the Four Families of Kokang (果敢四大家族).

Crackdown on Cybercrime

Operation 1027 expanded to Sagaing Region with PDF participation. Chinese authorities, dissatisfied with junta inaction on cyber fraud, began direct interventions. Myanmar authorities attempted to arrest cybercrime leader Ming Xuechang, who committed suicide during the operation. Ming’s family members were apprehended and transferred to Chinese authorities on November 16.

Operation 1027 Advances

The operation continued with alliance forces capturing numerous towns, strategic outposts, and border crossings from the junta. On December 10, Chinese authorities issued arrest warrants for ten principal suspects in Kokang telecom fraud operations.

Ceasefire Agreement

Under Chinese pressure, the junta transferred Bai Xueqian and other telecom fraud suspects to China. China mediated a fragile ceasefire between the junta and Three Brotherhood Alliance in northern Shan State, though violations remained frequent.

Fall of Myawaddy

Karen National Liberation Army (KNLA) and PDF joint forces captured the strategic Thai-Myanmar border town of Myawaddy. Concurrently, junta leader Min Aung Hlaing proposed reviving the long-stalled Myitsone Dam project in Kachin State to secure Chinese support.

Battle of Lashio

Tensions escalated again in northern Shan State as clashes erupted between the Myanmar junta and the Three Brotherhood Alliance (comprising the Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA), and Arakan Army (AA)) near Lashio on June 23. On August 3, 2024, the MNDAA captured the strategic stronghold of Lashio in northern Shan State, marking a significant blow to the military regime. The battle resulted in heavy casualties and the capture of several high-ranking officers.

Current Situation

The junta seeks to hold elections in 2025. China supports the elections, viewing them as essential for Myanmar’s stability. Despite losing control over vast territories, the junta maintains firm control of major urban areas. Cyber fraud and criminal activities remain rampant in Myawaddy and other regions. The National Unity Government (NUG) continues to operate in exile, receiving recognition from some Western entities but lacking substantial military or financial support from any nation.

| 1. State Administration Council (SAC)/Myanmar Military | ||

| Key Leader | Min Aung Hlaing | |

| Background |

• Staged a military coup in February 2021, overthrowing the democratically elected government • Has maintained significant political influence throughout Myanmar’s modern history • Engages in prolonged conflicts with ethnic armed organizations in contested regions |

|

| Position |

• Advocates national stability and a multi-party democratic system • Refutes the legitimacy of the 2020 general election, alleging electoral fraud • Cited these claims as justification for the coup |

|

| Controlled Territories |

• Nominally claims authority over all Myanmar territory • Maintains effective control of Naypyidaw (capital), major urban centers, and central regions • Exercises limited authority in ethnic armed organization strongholds and resistance-controlled areas |

|

| 2. National Unity Government (NUG) | ||

| Key Leaders | Duwa Lashi (President), Mahn Win Khaing Than (Prime Minister) | |

| Background |

• Established: April 16, 2021 • Composed of ousted elected representatives and ethnic minority politicians • Aims to oppose the military junta and seek international recognition |

|

| Position |

• Overthrow military rule and restore democratically elected government • Establish federal democracy with guaranteed ethnic minority rights • Advocate for international recognition and sanctions against the military regime |

|

| Controlled Territories |

• Does not directly control specific territories; operates through People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) conducting nationwide guerrilla warfare • Maintains influence in some rural areas and ethnic minority communities |

|

| International Support |

• Receives moral and political support from some Western nations and international organizations • Limited humanitarian aid from certain countries • Lacks formal recognition from UN and major international bodies as Myanmar’s legitimate government |

|

| People’s Defense Forces (PDFs) | Key Leaders | Led by the NUG Ministry of Defense, with decentralized local leadership structures |

| Background |

• Armed resistance forces that spontaneously emerged nationwide following the coup • Comprised of civilians from all walks of life, including students, workers, and professionals • Operate under NUG leadership while maintaining strong local autonomy, facing organizational and coordination challenges |

|

| Position |

• As NUG’s armed wing, shares its objectives to overthrow the military junta and establish a democratic federation • Collaborates with ethnic armed organizations against the military regime • Protects civilians and resists military suppression |

|

| Controlled Territories |

• Does not control major urban centers, primarily operating in rural, mountainous, and jungle areas • Established “liberated zones” and “people’s administrative structures” in some regions • Maintains limited scale and territorial control, frequently engaging in clashes with military forces |

|

| 3. Ethnic Armed Organizations (EAOs) – The Brotherhood Alliance | ||

| Alliance Overview | Key Leaders | The alliance does not have a single paramount leader, with decision-making through collective consultation among leaders of the three member organizations. Twan Mrat Naing, leader of the Arakan Army (AA), plays a more prominent coordinating role within the alliance. |

| Background |

• Established on November 20, 2016 • Initial objectives focused on countering military operations in ethnic regions and pursuing self-determination • Comprised of three ethnic armed groups: Arakan Army (AA), Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA), and Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) |

|

| Position |

• Primary goal of united resistance against the military junta to safeguard the interests of their respective ethnic groups • Initial focus potentially emphasizing ethnic autonomy and rights • Post-coup collaboration with resistance groups has expanded objectives to potentially include overthrowing the military regime |

|

| Controlled Territories |

• Primarily active within their respective ethnic states/regions, with no unified territorial control under the alliance structure • Collaborative operations may enable coordinated military efforts affecting broader geographical areas |

|

| Arakan Army (AA) | Key Leader | Twan Mrat Naing |

| Background |

• Founded in 2009 as the primary ethnic armed force in Rakhine State • Has engaged in prolonged conflict with the Myanmar military while steadily increasing its military capabilities • Maintains broad social foundations and local support within Rakhine State |

|

| Position |

• Pursue substantial autonomy or complete independence for Rakhine State • Protect the rights and interests of the Rakhine ethnic population • Oppose the military regime’s governance |

|

| Operational Areas | Rakhine State | |

| Myanmar National Democratic Alliance Army (MNDAA) | Key Leader | Pheung Kya-shin |

| Background |

• Primarily composed of the Kokang ethnic group, serving as the representative armed force in the Kokang region • Historically controlled the Kokang region before being expelled by the Myanmar military • Maintains complex connections with border areas of China |

|

| Position |

• Seeks to regain control of the Kokang region • Advocates for high autonomy for the Kokang people • Opposes the military government |

|

| Operational Areas | Northern Shan State, particularly the Kokang region | |

| Ta’ang National Liberation Army (TNLA) | Key Leader | Tar Bone Kyaw |

| Background |

• Represents the armed wing of the Ta’ang ethnic people, primarily operating in northern Shan State • Has engaged in conflicts with both the Myanmar military and other local armed groups |

|

| Position |

• Seek self-determination and autonomy for the Ta’ang (Palaung) people • Protect the rights and interests of the Ta’ang people • Oppose the military junta |

|

| Operational Areas | Northern Shan State | |

| 4. Other Important Ethnic Armed Groups | ||

| United Wa State Army (UWSA) | Key Leader | Bao Youxiang (Commander-in-Chief) |

| Background |

• Myanmar’s largest and most powerful ethnic armed organization with significant military capabilities and a high degree of autonomy • Controls economically developed territories with its own political, economic, and military systems |

|

| Position |

• Maintains de facto independent status while avoiding interference in Myanmar’s central politics • Seeks to preserve current autonomy through non-confrontation with the junta • Prioritizes self-preservation and stability maintenance in Wa State amid rising tensions |

|

| Controlled Areas | Northern and Eastern Shan State, Wa Region | |

| Kachin Independence Army (KIA) | Key Leader | Gam Shawng (Commander-in-Chief) |

| Background |

• Primary ethnic armed force in Kachin State with a long history of conflict with Myanmar’s government • Holds significant influence in Kachin State • Maintains alliances with other resistance forces against military rule |

|

| Position |

• Seeks autonomy for Kachin State • Protects interests of Kachin ethnic population • Has intensified opposition to military junta following 2021 coup |

|

| Active Area | Kachin State | |

| Shan State Progress Party/Northern Shan State Army (SSPP/SSA) | Key Leader | Wan Lek (Chairman) |

| Background |

• One of the armed organizations representing the Shan people, primarily active in northern Shan State • Maintains complex relationships with both the Myanmar military and other ethnic armed groups |

|

| Position |

• Advocates for ethnic autonomy and equality in Shan State • Protects the rights and interests of the Shan people • Maintains a cautious stance between the military government and resistance forces, avoiding large-scale conflicts while adjusting strategies according to evolving situations |

|

| Controlled Areas | Northern Shan State | |

| Pa-O National Liberation Army (PNLA) | Key Leader | Khun Myint Htun (Commander-in-Chief) |

| Background | Armed wing of the Pa-O National Organization (PNO), representing part of the Pa-O ethnic group | |

| Position |

• Seeks Pa-O self-administration and ethnic equality • Opposes military junta rule • May collaborate with NUG and PDFs to jointly oppose the military government |

|

| Controlled Areas | Southern Shan State | |